Your Brain's Shortcuts Are Silently Shaping Your Product and Results

How often have you seen this happen? A passionate and perhaps slightly frustrated piece of feedback reaches the team. It’s from an internal stakeholder, an important client, or a particularly vocal user from your support channels. The problem they describe is clear, and the pain is palpable. Suddenly, addressing this one issue becomes the team's unspoken priority. The urgency feels right and obvious.

But is it?

If we were to step back instead, and consult the broader data—like our analytics data, customer insights, and support ticket trends—we might find a different story. The urgent issue could simply be a rare edge case. Meanwhile, a less obvious, but far more impactful, opportunity may be waiting to be discovered in the quiet patterns of the data or through careful selection with all of our trade-offs out in the open.

This common scenario is a perfect example of a cognitive bias at play, likely the Availability Heuristic. Our brains give more weight to information that is recent, vivid, and easily recalled. The passionate complaint is memorable; the subtle signal in a dashboard is not. We act on the feedback we see, and in doing so, we allow the loudest voices to steer our product, potentially away from its most promising direction.

Why Your Brain Keeps Messing With Your Decisions

This isn’t a personal failing or a sign of incompetence. It’s simply how our brains work. We rely on mental shortcuts—heuristics and biases—to manage the overwhelming complexity of the world. Most of the time, they serve us well. But in product work, they can quietly lead us astray.

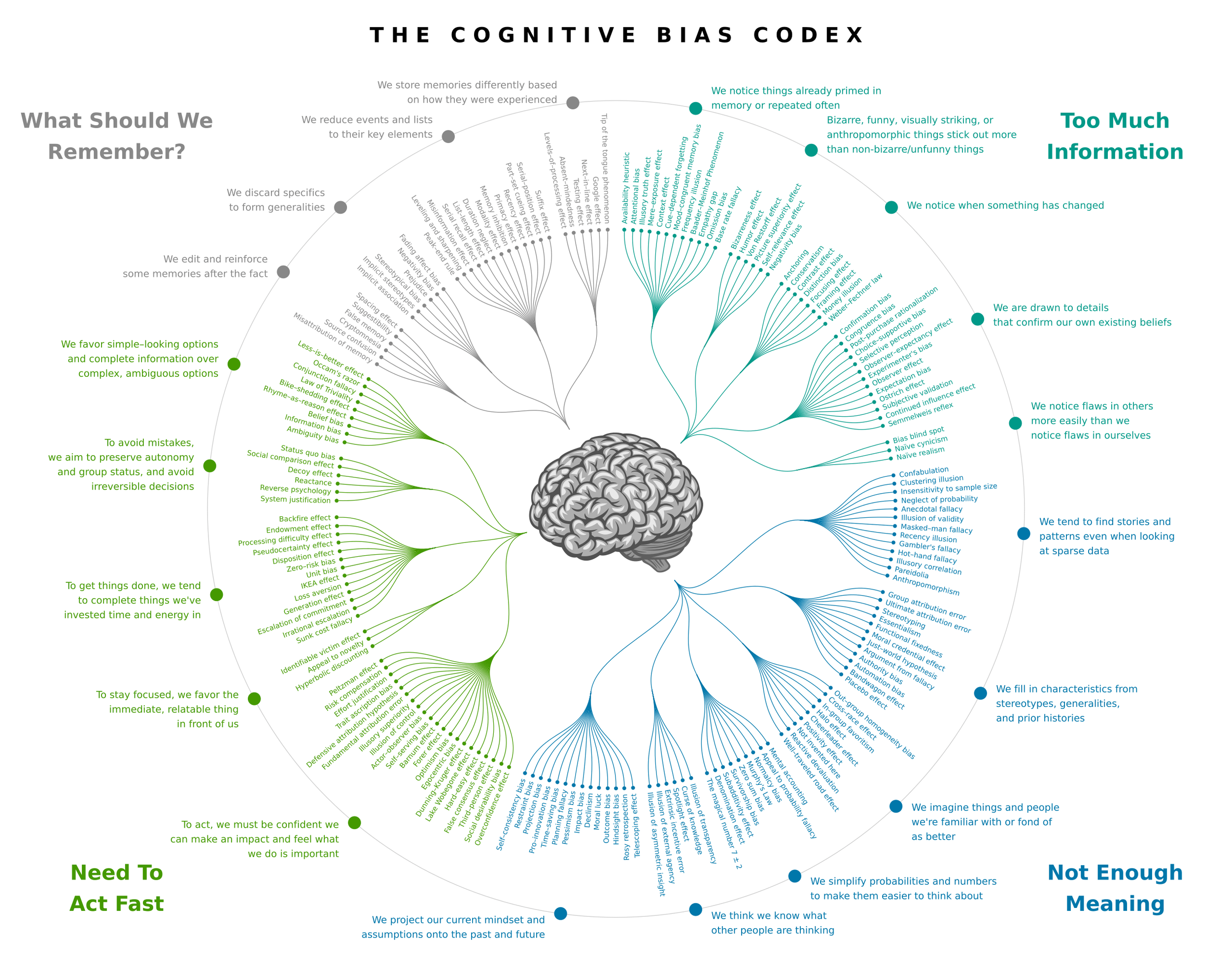

The Cognitive Bias Codex maps more than 180 of these shortcuts into a humbling graphic. They cluster around four survival problems: filtering overwhelming information, making meaning from too little data, acting quickly, and remembering what matters. These habits helped us as hunter-gatherers, but today they can sabotage decision-making.

For example: Confirmation Bias leads us to cherry-pick data that supports our pet feature. The Sunk Cost Fallacy convinces us to keep investing in a failing project because we've already spent so much on it. The IKEA Effect makes us overvalue a solution simply because we built it.

Without guardrails, these biases shape roadmaps more than strategy does.

An interactive version of the graphic is available at bias.wiki

How Great Teams Outsmart Their Biases

Knowing that our instincts are biased isn’t enough, though, the solution is not to try harder or to de-bug our brains. Great teams adopt behaviors that force our assumptions out into the open where they can be examined, discussed, and tested. The Codex isn't a list of flaws to memorize; it's a guide of sorts that highlights why we need to externalize our thinking. The codex is why many product practices are needed.

Data-informed decisions: Using data avoids, for example, overweighting vivid anecdotes.

Hypothesis-driven development: Surfaces assumptions and make disconfirmation possible.

Opportunity solution trees: Separates opportunities from solutions; countering pet ideas.

Testing early with real users: Early user feedback help us not overvalue what we built.

So, the best teams aren't those who believe they are unbiased; they are the ones who humbly accept their cognitive limits and build systems and behaviours to work around them.

Case Examples: Bias in Action

Case 1: The Dashboard That Wasn’t

A fintech team was pressured by a senior stakeholder to build an elaborate dashboard, because “every client asks for this.” Instead of building straight away, the team framed it as a hypothesis: We believe clients need a dashboard to understand their portfolio performance. In research, they discovered that 80% of clients only wanted better monthly summaries, not real-time dashboards. By reframing and testing, they avoided six months of wasted engineering time and shipped a lighter solution that delighted more users.

Case 2: Killing the Pet Project

A consumer app team had invested heavily in a gamification feature. Despite weak engagement metrics, they hesitated to cut it—classic sunk cost fallacy. By setting explicit “kill criteria” upfront, they created the space to re-evaluate. When adoption stalled below 5% after three months, the team sunsetted the feature and reinvested in onboarding, which boosted retention by 15%. The discipline of externalized assumptions helped them break free of bias and focus on outcomes.

Recommended Reading and Tools

Book only: Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman.

Book only: The Chimp Paradox, by Prof. Steve Peters

Book & Tools: Testing Business Ideas, by David J. Bland

Book & Tools: Design Sprints, by Jake Knapp at Google